Alleyway

(WIKIPEDIA)

An alley or alleyway is a narrow lane, path, or passage way, often for pedestrians only, which usually runs between or behind buildings in the older parts of towns and cities. The origin of the word alley is late Middle English: from Old French alee ‘walking or passage,’ from aler ‘go,’ from Latin ambulare ‘to walk’.[1]

Definition - Subjective

(WIKIPEDIA)

The word alley is used in two main ways:

- (1) It can refer to a narrow, usually paved, pedestrian path, often between the walls of buildings in towns and cities. This type is usually short and straight, and on steep ground can consist partially or entirely of steps.

- (2) It is also describes a very narrow, urban street, or lane, usually paved, which is often used by slow-moving vehicles, though more pedestrian-friendly than a regular street. There are two versions of this kind of alley:

- (a) A rear access or service road (back lane), which can also sometimes act as part a secondary vehicular network. Many Americans and Canadians think of an alley in these terms first.

- (b) A narrow street between the fronts of houses or businesses. This type of alley is found in the older parts of many cities, including American cities like Philadelphia and Boston (see Elfreth's Alley, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania). Many are open to traffic.

- The word is also used to describe a path or walk in a park or garden (French allée), though here it refers to a tree lined avenue.

In older cities and towns in Europe, alleys are often what is left of a medieval street network, or a right of way or ancient footpath. Similar paths also exist in some older North American towns and cities. In some older urban development in North America lanes at the rear of houses, to allow for deliveries and garbage collection, are called alleys. Alleys may be paved, or unpaved, and a blind alley is a cul-de-sac. Modern urban developments may also provide a service road to allow for waste collection, or rear access for fire engines and parking.

Because of geography steps (stairs) are the predominant form of alley in hilly cities and towns. This includes Pittsburgh (see Steps of Pittsburgh), Cincinnati (see Steps of Cincinnati), Seattle,[2] and San Franscisco[3] in the United States, as well as Hong Kong,[4] andRome.[5]

Some alleys are roofed, such as the traboules of Lyon, and the pedestrian passages through railway embankments in Britain. The latter follow the line of rights-of way that existed before the railway was built. Arcades are another kind of covered passage way and the simplest kind are no more than alleys to which a glass roof was added later, like, for example, Howey Place, Melbourne, Australia (see also Block Place, Melbourne). However, most arcades differ from alleys in that they are architectural structures built with a commercial purpose and are a form of shopping mall. All the same alleys have for long been associated with various types of businesses, especially pubs and coffee houses (see also Bazaar and Souq).

Europe - Older forms of Alleyway

(WIKIPEDIA)

Austria[edit]

Schönlaterngasse ("beautiful lantern alley") is a small winding alleyway in central Vienna. In the Middle Ages it was known as Straße der Herren von Heiligenkreuz ("street of the gentlemen of Heiligenkreuz"), as it passes the Heiligenkreuzer Hof ("Holy Cross courtyard"). The buildings along the alley date back to Baroque times. Schönlaterngasse originally terminated in an alleyway that was removed to make way for the Jesuitenkirche, upon which it was lengthened to Postgasse, where it still ends today.[95] ComposerRobert Schumann stayed at 7a Schönlaterngasse from October 1838 to April 1839.[96]

The so-called "beautiful lantern" is currently in Vienna’s City Museum, but a replica was installed in its original location in 1971. The street is home to several eating and drinking establishments. Schönlaterngasse has been on Austrian postage stamps four times. It can also be seen in Carol Reed's The Third Man [97]

France[edit]

Lyon's traboules[edit]

The traboules of Lyon are passageways that cut through a house or, in some cases a whole city block, linking one street with another. They are distinct from most other alleys in that they are mainly enclosed within buildings and may include staircases. While they are found in other French cities including Villefranche-sur-Saône, Mâcon, Chambéry, Saint-Étienne, Louhans, Chalon sur Saône and Vienne (Isère), Lyon has many more; in all there are about 500. The word traboule comes from the Latin trans ambulare, meaning “to cross”, and the first of them were possibly built as early as the 4th century. As the Roman Empire disintegrated, the residents of early Lyon—Lugdunum, the capital of Roman Gaul—were forced to move from the Fourvière hill to the banks of the river Saône when their aqueducts began to fail. The traboules grew up alongside their new homes, linking the streets that run parallel to the river Saône and going down to the river itself. For centuries they were used by people to fetch water from the river and then by craftsmen and traders to transport their goods. By the 18th century they were invaluable to what had become the city’s defining industry: textiles, especially silk.[98]

Nowadays, traboules are tourist attractions, and many are free and open to the public. Most traboules are on private property, serving as entrances to local apartments.

Germany[edit]

Spreuerhofstraße is the world's narrowest street, found in the city of Reutlingen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany.[99] It ranges from 31 centimetres (12.2 in) at its narrowest to 50 centimetres (19.7 in) at its widest.[100] The lane was built in 1727 during the reconstruction efforts after the area was completely destroyed in the massive city-wide fire of 1726 and is officially listed in the Land-Registry Office as City Street Number 77.[99][101]

Lintgasse is an alley (German: Gasse) in the Old town of Cologne, Germany between the two squares of Alter Markt and Fischmarkt. It is a pedestrian zone and though only some 130 metres long, is nevertheless famous for its medieval history. The Lintgasse was first mentioned in the 12th century as in Lintgazzin, which may be derived from basketmakers who wove fish baskets out of Linden tree barks. These craftsmen were called Lindslizer, meaningLinden splitter. During the Middle Ages, the area was also known as platēa subri or platēa suberis, meaning street of Quercus suber, the cork oak tree. Lintgasse 8 to 14 used to be homes of medieval knights as still can be seen by signs like Zum Huynen, Zum Ritter or Zum Gir. During the 19th-century the Lintgasse was called Stink-Linkgaß, a because of its poor air quality.[102]

Sweden[edit]

Gränd is Swedish for an alley and there are numerous gränder, or alleys in Gamla stan, The Old Town, of Stockholm, Sweden. The town dates back to the 13th century, with medieval alleyways, cobbled streets, and historic buildings. North German architecture has had a strong influence in the Old Town's buildings. Some of Stockholm's alleys are very narrow pedestrian footpaths, while others are very narrow, cobbled streets, or lanes open to slow moving traffic. Mårten Trotzigs gränd ("Alley of Mårten Trotzig") runs from Västerlånggatan and Järntorget up to Prästgatan and Tyska Stallplan, and part of it consists of 36 steps. At its narrowest the alley is a mere 90 cm (35 inches) wide, making it the narrowest street in Stockholm.[103] The alley is named after the merchant and burgher Mårten Trotzig (1559–1617), who, born in Wittenberg,[103]immigrated to Stockholm in 1581, and bought properties in the alley in 1597 and 1599, also opening a shop there. According to sources from the late 16th century, he was dealing in first iron and later copper, by 1595 had sworn his burgher oath, and was later to become one of the richest merchants in Stockholm.[104]

Possibly referred to as Trångsund ("Narrow strait") before Mårten Trotzig gave his name to the alley, it is mentioned in 1544 as Tronge trappe grenden ("Narrow Alley Stairs"). In 1608 it is referred to Trappegrenden ("The Stairs Alley"), but a map dated 1733 calls it Trotz gränd. Closed off in the mid 19th century, not to be reopened until 1945, its present name was officially sanctioned by the city in 1949.[104]

The "List of streets and squares in Gamla stan" provides links to many pages that describe other alleys in the oldest part of Stockholm; e.g. Kolmätargränd (Coal Meter's Alley);Skeppar Karls Gränd (Skipper Karl's Alley); Skeppar Olofs Gränd (Skipper Olof's Alley); and Helga Lekamens Gränd (Alley of the Holy Body).

United Kingdom - The Victorian Era & Influence

(WIKIPEDIA)

England[edit]

London[edit]

London has numerous interesting, historical alleys, especially, but not exclusively, in its centre; this includes The City, Covent Garden, Holborn, Clerkenwell, Westminster and Bloomsbury amongst others.

An alley in London can also be called a passage, court, place, lane, and less commonly path, arcade, walk, steps, yard, terrace, and close.[54] While both a court and close are usually defined as blind alleys, or cul-de-sacs, several in London are throughways, for example Cavendish Court, a narrow passage leading from Houndsditch into Devonshire Square, and Angel Court, which links King Street and Pall Mall.[55] Bartholomew Close is a narrow winding lane which can be called an alley by virtue of its narrowness, and because through-access requires the use of passages and courts between Little Britain, and Long Lane and Aldersgate Street.[56]

In an old neighbourhood of the City of London, Exchange Alley or Change Alley is a narrow alleyway connecting shops and coffeehouses.[57] It served as a convenient shortcut from the Royal Exchange on Cornhill to the Post Office onLombard Street and remains as one of a number of alleys linking the two streets. The coffeehouses[58] of Exchange Alley, especially Jonathan's and Garraway's, became an early venue for the lively trading of shares and commodities. These activities were the progenitor of the modern London Stock Exchange.

Lombard Street and Change Alley had been the open-air meeting place of London's mercantile community before Thomas Gresham founded the Royal Exchange in 1565.[59] In 1698, John Castaing began publishing the prices of stocks and commodities in Jonathan's Coffeehouse, providing the first evidence of systematic exchange of securities in London.

Change Alley was the site of some noteworthy events in England's financial history, including the South Sea Bubble from 1711 to 1720 and the panic of 1745.[60]

In 1761 a club of 150 brokers and jobbers was formed to trade stocks. The club built its own building in nearby Sweeting's Alley in 1773, dubbed the "New Jonathan's", later renamed the Stock Exchange.[61]

West of the City there are a number of alleys just north of Trafalgar Square, including Brydges Place which is situated right next to the Coliseum Theatre and just 15 inches wide at its narrowest point, only one person can walk down it at a time. It is the narrowest alley in London and runs for 200 yards (180 m), connecting St Martin's Lane with Bedfordbury in Covent Garden.[62]

Close by is another very narrow passage, Lazenby Court, which runs from Rose Street to Floral Street down the side of the Lamb and Flag pub; in order to pass people must turn slightly sideways. The Lamb & Flag in Rose Street has a reputation as the oldest pub in the area,[63] though records are not clear. The first mention of a pub on the site is 1772.[64] The Lazenby Court was the scene of an attack on the famous poet and playwright John Dryden in 1679 by thugs hired by John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester,[65] with whom he had a long-standing conflict.[66]

In the same neighbourhood Cecil Court has an entirely different character than the two previous alleys, and is a spacious pedestrian street with Victorian shop-frontages that links Charing Cross Road with St. Martin's Lane, and it is sometimes used as a location by film companies.[67][68]

One of the older thoroughfares in Covent Garden, Cecil Court dates back to the end of the 17th century. A tradesman's route at its inception, it later acquired the nickname Flicker Alley because of the concentration of early film companies in the Court.[69] The first film-related company arrived in Cecil Court in 1897, a year after the first demonstration of moving pictures in the United Kingdom and a decade before London’s first purpose built cinema opened its doors. Since the 1930s it has been known as the new Booksellers' Row as it is home to nearly twenty antiquarian and second-hand independent bookshops.

It was the temporary home of an eight-year-old Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart while he was touring Europe in 1764. For almost four months the Mozart family lodged with barber John Couzin.[70] According to some modern authorities, Mozart composed his first symphony while a resident of Cecil Court.[71]

North of the centre of London, Camden Passage is a pedestrian passage off Upper Street in the London Borough of Islington, famous because of its many antiques shops, and an antique market on Wednesdays and Saturday mornings. It was built, as an alley, along the backs of houses on Upper Street, then Islington High Street, in 1767.[72]

York[edit]

The Snickelways of York, in Yorkshire, often misspelt Snickleways, are a collection of small streets, footpaths, or lanes between buildings, not wide enough for a vehicle to pass down, and usually public rights of way. York has many such paths, mostly mediaeval, though there are some modern paths as well. They have names like any other city street, often quirky names such as Mad Alice Lane, Hornpot Lane Nether and evenFinkle Street (formerly Mucky Peg Lane). The word Snickelway was coined by local author Mark W. Jones in 1983 in his book A Walk Around the Snickelways of York, and is a portmanteau of the words snicket, meaning a passageway between walls or fences, ginnel, a narrow passageway between or through buildings, and alleyway, a narrow street or lane.[73] Although a neologism, the word quickly became part of the local vocabulary, and has even been used in official council documents.[74]

Rest of England[edit]

Outside of London there are numerous other words used locally to describe alleys, or narrow paths and lanes between, or behind buildings.

- In Manchester and Oldham, Lancashire, as well as Sheffield, Leeds and other parts of Yorkshire, Jennel, which may be spelt gennel or ginnel, is common.[75] In some cases, "ginnel" may be used to describe a covered or roofed passage, as distinct from an open alley.

- In East Sussex, West Sussex and Surrey, Twitten is used, for "a narrow path between two walls or hedges". It is still in official use in some towns including Lewes, Brighton and Cuckfield.[76][77]

- In the city of Brighton and Hove (in East Sussex), The Lanes is a collection of narrow lanes famous for their small shops (including several antique shops) and narrow alleyways. The area that is now the Lanes was part of the original settlement of Brighthelmstone, but they were built up during the late 18th century and were fully laid out by 1792.[78]

- In Nottinghamshire, north-west Essex and east Hertfordshire, twichell is common (See East Midlands English).

- In Liverpool, Lancashire the term entry, jigger or snicket is more common. "Entry" is also used in some parts of Lancashire, Manchester, though not in South Manchester. This usually refers to a walkway between two adjoining terraced houses, which leads from the street to the rear yard or garden. The term entry is used for an alley in Belfast, Northern Ireland (see The Belfast Entries).

- In Derbyshire and Leicestershire The word jitty or gitties is often found [79] and gulley is a term used in the Black Country.[80]

- In north-east England, including Bishop Auckland, County Durham; Durham; Hexham, Northumberland; Morpeth, Northumberland; Whitburn, South Tyneside; and Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Northumberland, alleys can be called chares. The chares and much of the layout of Newcastle's Quayside date from medieval times. At one point, there were 20 chares in Newcastle. After the great fire of Newcastle and Gateshead in 1854, a number of the chares were permanently removed although many remain in existence today. Chares also are still present in the higher parts of the city centre. According to "Quayside and the Chares" [81] by Jack and John Leslie, chares reflected their name or residents. "Names might change over the years, including Armourer's Chare which become Colvin's Chare". Originally inhabited by wealthy merchants, the chares became slums as they were deserted due to their "dark, cramped conditions". The chares were infamous for their insanitary conditions – typhus was "epidemic" and there were three cholera outbreaks in 1831-2, 1848–9 and finally in 1853 (which killed over 1,500 people).

- In Whitby, North Yorkshire "ghauts".[82]

- In Plymouth, Devon an alley is an opes.[83]

- In Shropshire (especially Shrewsbury) they are called shuts.[84]

- In Scunthorpe, Lincolnshire and Hull, East Yorkshire other terms in use are cuttings, 8-foots, 10-foots, and snicket.

- In North Yorkshire and County Durham, as in Scotland, an alley can be a wynd. There is a "Bull Wynd" in Darlington, County Durham and Lombards Wynd in Richmond, North Yorkshire.[85]

Scotland and Northern Ireland[edit]

In both places the Scots terms close, wynd, pend and vennel are general in most towns and cities. The term close has an unvoiced "s" as in sad. The Scottish author Ian Rankin's novel Fleshmarket Close was retitled Fleshmarket Alley for the American market. Close is the generic Scots term for alleyways, although they may be individually named closes, entries, courts and wynds. A close was private property, hence gated and closed to the public.

A wynd is typically a narrow lane between houses, an open throughway, usually wide enough for a horse and cart. The word derives from Old Norse venda, implying a turning off a main street, without implying that it is curved.[86] In fact, most wynds are straight. In many places wynds link streets at different heights and thus are mostly thought of as being ways up or down hills.

A pend is a passageway that passes through a building, often from a street through to a courtyard, and typically designed for vehicular rather than exclusively pedestrian access.[87] A pend is distinct from a vennel or a close, as it has rooms directly above it, whereas vennels and closes are not covered over.

A vennel is a passageway between the gables of two buildings which can in effect be a minor street in Scotland and the north east of England, particularly in the old centre of Durham. In Scotland, the term originated in royal burghscreated in the twelfth century, the word deriving from the Old French word venelle meaning "alley" or "lane". Unlike a tenement entry to private property, known as a "close", a vennel was a public way leading from a typical high street to the open ground beyond theburgage plots.[88] The Latin form is venella.

Snickelways of York

(WIKIPEDIA)

Definition

The snickelways themselves are usually small paths or lanes between buildings, not wide enough for a vehicle to pass down, and usually public rights of way. Jones provides the following definition for them:

A Snickelway is a narrow place to walk along, leading from somewhere to somewhere else, usually in a town or city, especially in the city of York.[1]

York has many such paths, mostly mediaeval, though there are some modern paths as well. They have names like any other city street, often quirky names such as Mad Alice Lane, Hornpot Lane Nether and even Finkle Street (formerly Mucky Peg Lane).

(WIKIPEDIA)

A Walk Around the Snickelways of York

In 1983 Jones devised a walk taking in 50 snickelways within the city walls. His book, A Walk around the Snickelways of York, soon became a local bestseller. It was unusual in being completely hand-written rather than using printed text, with hand-drawn illustrations, a technique which Jones explicitly acknowledged as inspired by the Pictorial Guides of Alfred Wainwright. At least nine editions of the book have been published, each revision incorporating necessary changes, such as the closure of snickelways which were not public rights of way or the opening of new paths.

The popularity of the book led to the author being called to present talks on the Snickelways, complete with a slide show. This in turn led to the publication in 1991 of an expanded, hardback book, The Complete Snickelways of York. This combined the original hand-written text with printed text and photographs. It also included information about Snickelways and other footpaths in the suburbs of York.[2]

Images - Snickelways of York

Mad Alice Lane - York

Numerous sources state that the Alice in etymological question was Alice Smith, and that she was executed in York Castle in the 1820s for being mad:

Travel Lady Magazine - "poor mad Alice Smith! The lane was her home until 1825 when she was taken to the castle and hanged for the ‘crime’ of insanity"

Wikipedia - "Mad Alice Lane... named after a woman hanged in 1823 for poisoning her husband"

Original Ghost Walk of York (as quoted in the Guardian) - "Alice Smith... confessed to crimes she didn't commit and was hanged"

Even the excellent Snickelways of York book claims that "Alice Smith lived here until 1825, when she was hanged at York Castle for being mad."

Sadly, like so many strange and fascinating local tales, this one has no basis in fact. The comprehensive Capital Punishment UK website shows that no-one called Alice Smith was executed in York in the 1820s. Indeed, as far as I can ascertain, no-one called Alice Smith has ever been executed in York. In the list of women executed publicly between 1800 and 1868, only two are called Alice, and neither of them died in York.

It seems a pity to debunk such a popular story, but I am a boffin after all. I don't like stories without evidence (and anyway, the truth is almost always more interesting). I'm almost tempted to offer my own guided* tours of York in which I assure the audience that everything I tell them is historically accurate and then lead them round the city in silence.

In the mean time, though, the mystery not only remains, but in fact expands. We know even less about Alice than we thought we did. I presume there must have been an Alice, but who was she, and why was she mad?

Posted 28th November 2012 by Liam Herringshaw

Mad Alice Lane

Nether Hornpot Lane - York

Nether Hornpot Lane

Finkle Street (Formerly known as Mucky Peg Lane) - York

Links -

Other Snikelways - York

|

| Coffee Yard is the longest Snickelway - nearly 220 feet (67 metres) long.[1] |

|

| Pope's Head Alley – only 2 ft 7 in (790 mm) wide.[1] |

|

| The shortest Snickelway,Hole-in-the-Wall, after the adjacent pub, which may be named after the nearbyBootham Bar.[1] |

|

| Mad Alice Lane (also known as Lund's Court) – named after a woman hanged in 1823 for poisoning her husband.[3] |

Other Links - http://www.yorkwalk.co.uk/

Cecil Court

Yesterday, we had the pleasure of filming in London’s historic Cecil Court.

This feels like the icing on the cake to me. We've filmed in some atmospheric and diverse bookshops so far, all of which are genuinely special in their own ways, but Cecil Court occupies a unique place in the history of English bookshops.

It is possible that you may never have heard of Cecil Court, or may be unaware that the whole Charing Cross area (a pigeon’s flap away from Trafalgar Square) is a hive of independent  bookshops. But it is. And it was throughout the whole of the twentieth century. Fashions, technologies and world wars have come and gone (as indeed have high street book chains) but Cecil Court has remained. It is a time capsule of late Victorian shop fronts; a chocolate box alleyway, lined with inviting windows displaying rare antique books and modern first editions alike.

bookshops. But it is. And it was throughout the whole of the twentieth century. Fashions, technologies and world wars have come and gone (as indeed have high street book chains) but Cecil Court has remained. It is a time capsule of late Victorian shop fronts; a chocolate box alleyway, lined with inviting windows displaying rare antique books and modern first editions alike.

bookshops. But it is. And it was throughout the whole of the twentieth century. Fashions, technologies and world wars have come and gone (as indeed have high street book chains) but Cecil Court has remained. It is a time capsule of late Victorian shop fronts; a chocolate box alleyway, lined with inviting windows displaying rare antique books and modern first editions alike.

bookshops. But it is. And it was throughout the whole of the twentieth century. Fashions, technologies and world wars have come and gone (as indeed have high street book chains) but Cecil Court has remained. It is a time capsule of late Victorian shop fronts; a chocolate box alleyway, lined with inviting windows displaying rare antique books and modern first editions alike.

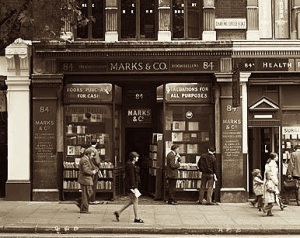

I visited London several times through the years before I was even aware of Cecil Court. Somehow I managed to miss it on each trip, which seems ridiculous now, but it’s true. Then I read Helene Hanff’s magical ’84 Charing Cross road’ (a book comprising the real correspondence between its eccentric USA-bound author and the London bookshop of the title between 1949 and 1969) and was compelled to pursue a pilgrimage to the eponymous shop . . . which is now a pizza place.

Cecil Court is just off Charing Cross road, and its shops have largely avoided the fate of Marks & Co at number 84. But at the very edge of Cecil Court, a garish burger bar called Byron intrudes ominously on the period scenery, as if a multi-coloured fast food joint has fallen through a time portal and landed in Victorian London. You can turn your back on it, and imagine its not there. But the paranoia whispers that one day, maybe we will have to ignore more than just Byron. Maybe we’ll have to ignore a Starbucks as well . . . and a Subway or two . . . perhaps a gaggle of mobile phone shops.

largely avoided the fate of Marks & Co at number 84. But at the very edge of Cecil Court, a garish burger bar called Byron intrudes ominously on the period scenery, as if a multi-coloured fast food joint has fallen through a time portal and landed in Victorian London. You can turn your back on it, and imagine its not there. But the paranoia whispers that one day, maybe we will have to ignore more than just Byron. Maybe we’ll have to ignore a Starbucks as well . . . and a Subway or two . . . perhaps a gaggle of mobile phone shops.

largely avoided the fate of Marks & Co at number 84. But at the very edge of Cecil Court, a garish burger bar called Byron intrudes ominously on the period scenery, as if a multi-coloured fast food joint has fallen through a time portal and landed in Victorian London. You can turn your back on it, and imagine its not there. But the paranoia whispers that one day, maybe we will have to ignore more than just Byron. Maybe we’ll have to ignore a Starbucks as well . . . and a Subway or two . . . perhaps a gaggle of mobile phone shops.

largely avoided the fate of Marks & Co at number 84. But at the very edge of Cecil Court, a garish burger bar called Byron intrudes ominously on the period scenery, as if a multi-coloured fast food joint has fallen through a time portal and landed in Victorian London. You can turn your back on it, and imagine its not there. But the paranoia whispers that one day, maybe we will have to ignore more than just Byron. Maybe we’ll have to ignore a Starbucks as well . . . and a Subway or two . . . perhaps a gaggle of mobile phone shops.

Maybe one day there will be just one left: The Last Bookshop. It doesn't bear thinking about.

Of course, our little film is all about exploring that imagined future on a larger scale: not just the last bookshop in Cecil Court, but the last one in the world. Perhaps more importantly, our film is also about exploring what is captivating about bookshops now, and recognizing that heritage.

As with Hall’s in Tunbridge Wells, Cecil Court is the perfect embodiment of this history. It is mind boggling to think, for example, that Watkins Books was established in the 1890s, and has been trading from 21 Cecil Court continuously since 1901. The same bookshop we can visit today could also have been visited every week right back to the year Queen Victoria died.

Cecil Court connects us with our past, preserving  a little bit of a London that is otherwise almost gone. To me, this seems most tangible in David Drummond’s aptly-named shop ‘Pleasures of Past Times.’ In David’s own words, the shop is “festooned with the ephemera of show business including famous performers of the past.” The posters and bills of shows long since retired from the stage peer down at you, replete with smiling sepia faces from silent films and music halls. You can smell the greasepaint, feel the warmth of the limelight . . . until a sign on the counter regarding obtrusive mobile phone calls brings you crashing back to the modern day.

a little bit of a London that is otherwise almost gone. To me, this seems most tangible in David Drummond’s aptly-named shop ‘Pleasures of Past Times.’ In David’s own words, the shop is “festooned with the ephemera of show business including famous performers of the past.” The posters and bills of shows long since retired from the stage peer down at you, replete with smiling sepia faces from silent films and music halls. You can smell the greasepaint, feel the warmth of the limelight . . . until a sign on the counter regarding obtrusive mobile phone calls brings you crashing back to the modern day.

a little bit of a London that is otherwise almost gone. To me, this seems most tangible in David Drummond’s aptly-named shop ‘Pleasures of Past Times.’ In David’s own words, the shop is “festooned with the ephemera of show business including famous performers of the past.” The posters and bills of shows long since retired from the stage peer down at you, replete with smiling sepia faces from silent films and music halls. You can smell the greasepaint, feel the warmth of the limelight . . . until a sign on the counter regarding obtrusive mobile phone calls brings you crashing back to the modern day.

a little bit of a London that is otherwise almost gone. To me, this seems most tangible in David Drummond’s aptly-named shop ‘Pleasures of Past Times.’ In David’s own words, the shop is “festooned with the ephemera of show business including famous performers of the past.” The posters and bills of shows long since retired from the stage peer down at you, replete with smiling sepia faces from silent films and music halls. You can smell the greasepaint, feel the warmth of the limelight . . . until a sign on the counter regarding obtrusive mobile phone calls brings you crashing back to the modern day.

Hopefully, ‘The Last Bookshop’ will portray the magic and splendor of these terrific shops. But the truth can still be found around Charing Cross. And as people question the relevance of bookshops (and indeed books) in the modern marketplace, here we can still enjoy what we might one day be missing.

In particular, our Cecil Court filming has taken place in Goldsboro Books (specialists in signed first editions) and in David Drummond’s shop ‘Pleasures of Past Times.’ Both splendid establishments, worthy of your custom. We would like to thank the Davids twain for their help.

Other United Kingdom References :

England :

Edinburg :

http://www.bpra.org.uk/photos.htmlImage References - United Kingdom

European - Alleyway's

(WIKIPEDIA)

Sweden

Stockholm

History of Stockholm

The history of Stockholm, capital of Sweden, for many centuries coincided with the development of what is today known as Gamla stan, the Stockholm Old Town. Parts of this article, as a consequence, therefore overlap with the History of Gamla stan.

Furthermore, Stockholm's raison d'être, always was to be the Swedish capital and by far the largest city in the country, and, consequently, retelling the story of the city without including some of the history of Sweden is virtually impossible.

Origins[edit]

The name 'Stockholm' easily splits into two distinct parts – Stock-holm, "Log-islet", but as no serious explanation to the name has been produced, various myths and legends have attempted to fill in the gap. According to a 17th-century myth the population at the viking settlement Birka decided to found a new settlement, and to determine its location had a log bound with gold drifting in Lake Mälaren. It landed on present day Riddarholmen where today the Tower of Birger Jarl stands, a building, as a consequence, still often erroneously mentioned as the oldest building in Stockholm.[1] The most established explanation for the name are logs driven into the strait passing north of today's old town which dendrochronological examinations in the late 1970s dated to around 1000. While no solid proofs exists, it is often assumed the Three Crown Castle, which preceded the present Stockholm Palace, originated from these wooden structures, and that the medieval city quickly expanded around it in the mid 13th century.[2] In a wider historical context, Stockholm can be thought of as the capital of the Lake Mälaren Region, and as such can trace its origin back to at least two much older cities: Birka (c. 790–975) and Sigtuna, which still exists but dominated the region c. 1000–1240 — a capital which has simply been relocated at a number of occasions.[3]

Middle Ages[edit]

Main article: Stockholm during the Middle Ages

The name Stockholm first appears in historical records in letters written by Birger jarl and king Valdemar dated 1252. However, the two letters give no information about the appearance of the city and events during the following decades remain diffuse. While the absence of a perpendicular city plan in medieval Stockholm seem do indicate a spontaneous growth, it is known German merchants invited by Birger jarl played an important role in the foundation of the city.[5][6] Under any circumstance, during the end of the 13th century, Stockholm quickly grew to become not only the largest city in Sweden, but also the de facto Swedish political centre and royal residence. So, from its foundation, Stockholm has been the largest and most important Swedish city, inseparable from and dependent of the Swedish government.[7]

During the Kalmar Union (1397–1523), controlling Stockholm was crucial to anyone aspiring to control the kingdom, and the city was consequently repeatedly besieged by various Swedish-Danish fractions. In 1471, Sten Sture the Elder defeated Christian I of Denmark at the Battle of Brunkeberg only to lose the city to Hans of Denmark in 1497. Sten Sture managed to seize power again in 1501 which resulted in a Danish blockade lasting 1502–1509 and eventually a short peace. Hans' son Christian II of Denmark finally conquered it in 1520 and had many leading nobles and burghers of Stockholm beheaded in the so-called Stockholm Bloodbath. When King Gustav Vasa finally besieged and conquered the city three years later, an event which ended the Kalmar Union and the Swedish Middle Ages, he noted every second building in the city was abandoned.[9]

By the end of the 15th century, the population in Stockholm can be estimated to 5,000–7,000 people, which made it a relatively small town compared to several other contemporary European cities. On the other hand, it was far larger than any other city in Sweden. Many of its inhabitants were Germans and Finns, with the former forming a political and economic elite in the city.[10]

During the Middle Ages, export was administered mostly by German merchants living by the squares Kornhamnstorg ("Grain Harbour Square") and Järntorget ("Iron Square") on the southern corner of the city. Regional peasantry supplied the city with food and raw materials, while the craftsmen in the city produced handicrafts, most of whom lived by the central square Stortorget or by the oldest two streets in Stockholm, the names of which still reflects their trade: Köpmangatan ("Merchant Street") and Skomakargatan ("Shoemaker Street") in the central part of the city. Other groups lived by the eastern or western thoroughfares, Västerlånggatan and Österlånggatan.[11]

Early Vasa era[edit]

Main article: Stockholm during the early Vasa era

See also: Historical fires of Stockholm

After Gustav Vasa's siege of Stockholm, he restored the privileges of the city which was beneficiary to the burghers of the city. The king maintained his control over the city by controlling the elections of aldermen and magistrates. By the mid-century, the numbers of officials increased in order to make the management of the city more professional and to ensure the state-controlled trade. Stockholm thus lost much of the independence it had had during the Middle Ages and became politically and financially bound to the state.[12] During the reign of his sons (1561–1611), the city council remained escorted by a royal representative and both magistrates and aldermen were appointed by the king.[13]

Gustav Vasa invited the clergyman Olaus Petri (1493–1552) to become the city secretary of Stockholm. With the two side-by-side, the new ideas of the Protestant Reformation could be quickly implemented, and sermons in the church where held in Swedish starting in 1525 and Latin abolished in 1530. A consequence of this development was a need for separate churches for the numerous German and Finnish-speaking citizens and during the 1530 the still-existent German and Finnish parishes were created. The king was, however, not favourably disposed to older chapels and churches in the city, and he ordered churches and monasteries on the ridges surrounding the city to be demolished, together with the numerous charitable institutions.[14]

Because Stockholm had a city wall, it was exempted from the tax paid by other Swedish cities. During the reign of Gustav Vasa the city's fortifications were reinforced and in theStockholm Archipelago, Vaxholm was created to guard the inlet from the Baltic. While the medieval structure of Stockholm remained mostly unaltered during the 16th century, the city's social and economic importance grew to the extent that no king could permit the city to determine its own faith – the most important export item being bar iron and the most important destination Lübeck.[15] During the reign of Vasa's sons, trade led many Swedes to settle in the city, but the trade and the capital needed to control it was largely in the hands of the king and German merchants from Lübeck and Danzig. Throughout the era, Sweden could hardly claim the level of government and bureaucracy requisite to a capital in the modern sense, but Stockholm was the kingdom's strongest bastion and the king's main residence. As Eric XIV's pretensions were on par with those of Renaissance princes on the continent, he afforded himself the largest court his finances could possibly support, and the royal castle was thus the biggest employer in the city.[13]

Around 1560–80, most of the citizens, some 8.000 people, still lived on Stadsholmen. This central island was at this time densely settled and the city was now expanding on the ridges surrounding the city. Stockholm had no private palaces at this time and the only larger buildings were the castle, the church, and the former Greyfriars monastery on Riddarholmen. The surrounding ridges, unable to boast a single timber framed building, were mostly used for activities that either required a lot of space, produced odours, or could cause fire. Even though some burghers had secondary residences outside the city, the population living on the ridges, perhaps a quarter of the city's population, were mostly poor, including the royal personnel occupying the ridges north of the city.[13]

Great Power era[edit]

Main article: Stockholm during the Great Power Era

Following the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), Sweden was determined never to repeat the embarrassment experienced following the death of Gustavus II Adolphus (1594–1632) when Stockholm, still medieval in character, caused hesitation on whether to invite foreign statesmen for fear the lamentable appearance might undermine the nation's authority. Therefore, Stockholm saw many ambitious city plans during the era, of which those for the ridges surrounding today's old town still stands. In accordance to the mercantilism of the era, trade and industry was concentrated to cities where it was easier to control, and Stockholm was of central importance. In a letter in 1636, Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna (1583–1654) wrote that evolving the Swedish capital was a prerequisite for the nation's power and strength and that this would bring all the other cities on their feet. Increased state intervention on city level was not unique to Sweden at this time, but it was probably more prominent in the case of Stockholm than anywhere else in Europe. To this end, the government of the city was reformed and the former volunteered magistrates gradually replaced by professionals with a theoretical education.[16]

Age of Liberty (1718–1772)[edit]

Main article: Stockholm during the Age of Liberty

| Population[23] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Late 17th century | 55–66.000 | |

| Around 1720 | 45.000 | |

| Mid 18th century | 60.000 | |

| Mid 19th century | 90.000 | |

| Social stratification 1769–1850 (per cent)[23] | ||

| Class | 1769 | 1850 |

| Upper | 13 | 7 |

| Middle | 40 | 12 |

| Lower | 47 | 81 |

Following the Greater Wrath and the Treaty of Nystad in 1722, Sweden's role as a major European power was over, and the decades that followed brought even more disasters. Black death and the sufferings caused by the Great Northern Wars made Stockholm the capital of a shrinking nation, despair which would deepen even further when Sweden lost Finland in 1809. Notwithstanding Sweden's partial recover of spirit with the union with Norway in 1814, during the period 1750–1850, Stockholm was a stagnating city, with a dwindling population and widespread unemployment, marked by ill-health, poverty, alcoholism, and rampant mortality. The Mälaren region lost in influence to the benefit of south-western Sweden, and as population and welfare dwindled in the capital, there was a leveling of social classes.[24] Wars and alcohol abuse resulted in a surplus of women during the period, with widows outnumbering widowers six to one in 1850. Stockholm was marked by an absence of children, caused by the number of unmarried people and high infant mortality. Average length of life was limited to 44, but those who survived infancy were likely to get about as old as people do today, except those born to a life of hard labour.[23]

A stratification into three social groups can be made for this era :

- individuals of rank and officers

- craftsmen, small-scale entrepreneurs, and officials

- journeymen, assistants, workers, soldiers, servants, paupers, and prisoners.

Women were associated with their husband's status. However, as craftsmen saw their status sink with the introduction of industrialism, the proletarian class grew during the period. There also was an economic segregation in the city, with the present old town and the lower parts of Norrmalm being the wealthiest (more than 150% above average); the suburbs (today part of central Stockholm) were poor (50% below average).[23]

During the 18th century the Mercantile model introduced the previous century was further developed, with domestic production promoted by loans and bounties and import limited to raw materials not available in Sweden by tolls. The era saw the rise of the so-called "Skeppsbro Nobility" (Skeppsbroadeln), the wealthy wholesalers at Skeppsbron who made a fortune by delivering bar iron to the international market and by controlling the chartered companies.[26] The most successful of them was the Swedish East India Company (1731–1813) which had its headquarters in Gothenburg, but was of significant importance to Stockholm because of the shipbuilding yards, the trade houses, and the exotic products imported by the company. Furthermore, before these ships left Stockholm some 100–150 men per ship were recruited, most of them in the city, and as a single trip to China would take 1–2 years the company had a huge impact on Stockholm during this era.[27]

During the 18th century, several devastating fires destroyed entire neighbourhoods which resulted in building codes being introduced. They improved fire safety by prohibiting wooden buildings and further embellished the city by implementing the 17th century city plans. In the old town, the new royal palace was gradually completed and the exterior of the Storkyrkanchurch was adopted to it. The skilled artists and craftsmen working for the royal court formed an elite which considerably raised the artistic standards in the capital.[25]

Gustavian era (1772–1809)[edit]

During the enlightened absolute monarchy of Gustav III Stockholm managed to maintain its role as the political centre of Sweden and developed culturally.

The king had a great interest for the city's development. He created the Gustav Adolf square and had the Royal Opera inaugurated there in 1782 — in accordance to the original intentions of Tessin the Younger for a monumental square north of the palace. The façade of Arvfurstens palats on the opposite side is identical to the now replaced façade of the opera.[25]

The neoclassical bridge Norrbro, designed by Erik Palmstedt and constructed 1741–1807, was an ambitious project that caused the centre of the city to gradually move out of the medieval city.[28]

The colourful and often burlesque descriptions of Stockholm by troubadour and composer Carl Michael Bellman are still popular.

The period ended as King Gustav IV Adolf was deposed in 1809 in a coup d'état. The loss of Finland that same year meant Stockholm ceased to be the geographical centre of the Swedish kingdom.[28]

Early industrial era (1809–1850)[edit]

For Stockholm, the early 19th century meant the only larger-scale projects to be realised were those initiated by the military which favoured a more stiff classicism, the local Swedish version of the Empire style (in Sweden namedKarl Johansstil after King Charles XIV John). The architects dominating the era, Fredrik Blom and Carl Christoffer Gjörwell, both were commissioned by the military. Due to the general stagnation, few other constructions were realised — in average ten smaller residential buildings per year — additions which the ambitious city plans of the 17th century could easily handle.[28]

During the later half of the 18th century real income dwindled to reach an all time low in 1810 when it corresponded to roughly half that of the 1730s; public officials being those worst affected.[24] Norrköping became the greatest manufacturing city of Sweden and Gothenburg developed into the key trading port because of its location on the North Sea.

Most people still lived within the present Old Town, with a growth along the eastern shore. Population also grew on the surrounding ridges, more so in the wealthy district Norrmalm and less so in the poor district Södermalm.[23]However, many of the ridges surrounding the city were slums mostly rural in character without water and sewage and frequently ravaged by cholera.[28]

Late industrial era (1850–1910)[edit]

In the second half of the century, Stockholm regained its leading economic role. New industries emerged, and Stockholm transformed into an important trade and service centre, as well as a key gateway point within Sweden.

While steam engines were introduced in Stockholm in 1806 with the Eldkvarn mill, it took until the mid-19th century for industrialization to take off. Two factories, Ludvigsberg and Bolinder, constructed in the 1840s were followed by many others, and the economic development that succeeded resulted in some 800 new buildings being constructed 1850–70 — many of which were located in the Klara district and subsequently demolished in theRedevelopment of Norrmalm 1950–70.[28]

During the 1850s and 1860s, gas works, sewage, and running water was introduced. Many street were paved, including Skeppsbron and Strandvägen, and the railway brought Stockholm closer to continental Europe — an event which additionally lead to the creation of the first suburb Liljeholmen where railway workshops were located. As the railway was extended further north, Stockholm Central Station was inaugurated in 1871. The first horse-pulled trams were introduced in 1877. Long before the railway, steam engines became common on boats which resulted in many summertime residences being built around Stockholm. But the booming urban development was also notable in central Stockholm where several prominent Neo-Renaissance buildings were built, including the Academy of Music and Södra Teatern.[28]

In 1866, a commission led by Albert Lindhagen produced a city plan for the ridges (malmarna) designed to offer citizens light, fresh air and access to Swedish nature by mean of parks and plantations. To this goal, he proposed a system of esplanades culminating in Sveavägen, a 2 km long and 70 m wide boulevard inspired by Champs Elysées. 1877–80 new city plans were finally passed for central Stockholm, which made the city well-prepared for the major expansion that followed.[28] During the 1880s more than 2.000 buildings were added on the ridges and the population grew from 168.000 to 245.000.[29] At the end of the century, less than 40 per cent of the residents were born in Stockholm.

While this demand for housing was mostly dealt with by private entrepreneurs who built on pure speculation, street width and building heights were strictly regulated by the new city plans which ensured the city that evolved was given a uniform design. A trend initiated by the Bünsow House at Strandvägen, the 1880s saw many monumental brick buildings evolve, including Gamla Riksarkivet and the Norstedt Building on Riddarholmen. Before the end of the decade most new buildings were equipped with electricity and telephones were increasingly common. During the 1890, the Neo-Renaissance plaster architecture was replaced by structures in brick and natural stone, largely inspired by French Renaissance architecture. Around what still was factories outside the customs of Stockholm, shacks whose sanitary conditions defied all description evolved. Before the end of the century, however, these were transformed into municipal societies, which facilitated regulation of health and construction, and by the turn of the century the expansion had continued far beyond the city limits, with villa suburbs initiated by individuals adding a mix of purely speculative structures and more qualitative ambitions. The new century saw the introduction of Art Nouveau with the Central Post Office Building by Boberg (1898–1904) and Neo-Baroque with the Riksdag (1894–1906). Throughout the 1910s, trams were electrified and cars were rolling on the streets of Stockholm.[29]

During this period, Stockholm further developed as a cultural and educational centre. In the 19th century, a number of scientific institutes opened in Stockholm, for example the Karolinska Institute. The General Art and Industrial Exposition, an international exhibition of World's Fair status, was held on the island of Djurgården in 1897.

Marten Trotzigs Grand - Stockholm, Sweden

(WIKIPEDIA)

Mårten Trotzigs gränd (Swedish: "Alley of Mårten Trotzig") is an alley in Gamla stan, the old town of Stockholm, Sweden. Leading from Västerlånggatan and Järntorget up to Prästgatan and Tyska Stallplan, the width of its 36 steps tapers down to a mere 90 cm, making the alley the narrowest street in Stockholm.[1]

History

The alley is named after the merchant and burgher Mårten Trotzig (1559–1617), who, born in Wittenberg,[1] immigrated to Stockholm in 1581, and bought properties in the alley in 1597 and 1599, also opening a shop there. His original German name is said to have been Traubtzich, but he is also mentioned under various other names, such as Trutzich, Trutzigh, Trusick, Trotuitz,Tråtzich, Trotzigh, and Tråsse. According to sources from the late 16th century, he was dealing in first iron and later copper, by 1595 had sworn his burgher oath, and was later to become one of the richest merchants in Stockholm. He was however beaten to death during a trip to Kopparberg in 1617.[2]

Possibly referred to as Trångsund ("Narrow strait") before Mårten Trotzig gave his name to the alley, it is mentioned in 1544 as Tronge trappe grenden ("Narrow Alley Stairs"). In 1573 a property is referred to as situated...

- Old Swedish : ...norden för Järntorgitt näst Lång gaten westen till vp med then trånge trappe grändh, som löper vp till Suarttmuncke clöster.

- Modern Swedish : ...norr om Järntorget intill Långa gatan i väster upp för den trånga trappans gränd, som löper upp till svartmunkeklostret.

- English : ...north of 'the iron square' next to 'the Long street to the west' up the narrow stairs alley, running up to the Blackfriars abbey.

In 1608 it is referred to Trappegrenden ("The Stairs Alley"), but a map dated 1733 calls it Trotz gr[änd], a name which, using various alternative spellings, was to remain the name used, save for an attempt in the late 18th century to inexplicably rename it Kungsgränden ("The Kings Alley"). Closed off in the mid 19th century, not to be reopened until 1945, its present name was officially sanctioned by the city in 1949.[2]

|

| Mårten Trotzigs Gränd |

No comments:

Post a Comment